Plants and Animals in China

First-person accounts of China often discuss the environmental impacts of economic growth and social pressures. They are certainly in evidence: brown river, denuded banks, flowing sluggishly through industrial landscapes beneath smoke-stained red skies. To be honest, those scenes were much less prevalent than I expected: smaller rivers could be surprisingly clean and green.

First-person accounts of China often discuss the environmental impacts of economic growth and social pressures. They are certainly in evidence: brown river, denuded banks, flowing sluggishly through industrial landscapes beneath smoke-stained red skies. To be honest, those scenes were much less prevalent than I expected: smaller rivers could be surprisingly clean and green.

However, I was really surprised by the huge disparity in the respect shown for living things amidst the landscapes

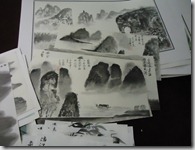

The Chinese dote on their plants. Driving into cities, every broad boulevard is lined with trees and flowering bushes, each kilometer tended by three of four gardeners sweeping, raking, trimming, and tending. Broad trees have their limbs supported by poles anchored into the ground around them: the Old Banyon Tree is a famous source of luck and longevity if you walk around it once (no word on whether clockwise or counterclockwise). Hotels and public spaces have soaring floral arrangements; the shape, color, and shadow of blossoms are celebrated in art and dance.

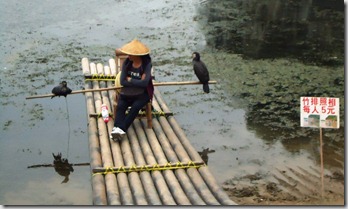

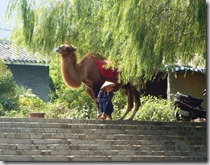

Chinese are hard on their animals. Several areas that I visited are in the tropical south, yet birds were few and well hidden. Farms have a few desultory oxen or sheep; only the occasional dog roams the street. Outdoor shopping areas have exotic animals to pose with – monkeys in clown costumes, peacocks with tail feathers pinned up, a camel out of all likelihood. Mynah birds fill cages in front of shops; occasional flocks of ducks cluster in reeds along rivers.

I’m not sure what spiritual or moral sense drives this division, but it seemed universal. It’s strange to see park grounds with only the occasional butterfly, silence where there should be birds, strollers without pets. I’m doing a bit of reading that I hope will sort the mystery, but it leaves the impression that animals simply exist for food and fun.

Labels: China